Along Cuba’s sparkling southern Caribbean coast, our taxi wound its way through seemingly endless sugarcane fields, the abandoned partially-completed Juraguá nuclear Power Plant just a prospect on the horizon.

[Essay continues below…]

William, a resident of Havana, had agreed to drive Becca and me the 238km, undeterred by the fact that the plant did not appear on most maps and that we had no GPS to guide us. I expected we would have difficulty finding it, but William brought the Lada to a halt several times, craning his neck out into the stifling August heat to ask for guidance from passersby, “¡Buen día!” he called out. I was struck by the alacrity with which these kind strangers offered their assistance.

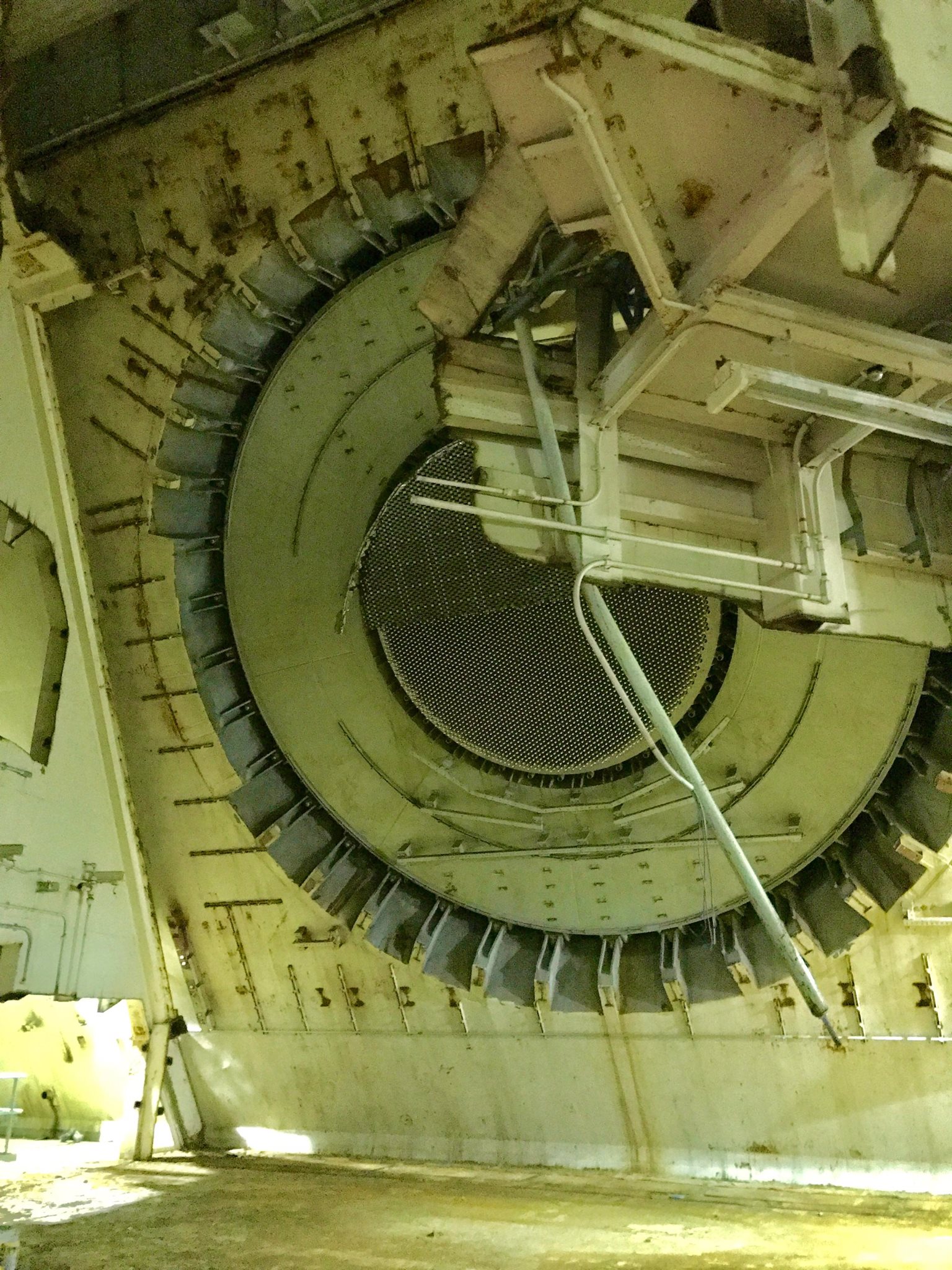

As we continued our journey, the landscape seemed to echo the ambitions and disappointments of Cuba’s nuclear past. From my research, I knew that construction on Juraguá began in 1983, bankrolled by the Soviet Union. Juraguá was to house two Soviet-designed pressurized VVER-440 V318 water reactors that would produce as much as 15 percent of Cuba’s electricity needs. The design was to be state of the art and differed from the Chernobyl-era RBMK reactors in that its core and fuel elements were to be contained within a pressurized steel dome.

Just as Ukraine’s Chernobyl had the neighboring city of Pripyat and Lithuania’s Ignalina facility had Visaginas, Juraguá was to be accompanied by a planned city. Dubbed Ciudad Nuclear, the city was to contain 4,200 homes to house the plant’s scientists, engineers, and other workers and their families. Construction began on high-rise towers, some 15-20 stories in height.

By the time we reached the end of a narrow, tattered concrete road, I thought of President Fidel Castro’s words—he had called the project “the undertaking of the century.” By 1992, with $1.1 billion USD invested, approximately 90 percent of Juraguá’s foundations and 40 percent of its machinery had been installed. However, the project stalled in 1992 when funding dried up due to the collapse of the Soviet Union.

At mid-afternoon, Juraguá’s faded yellow dome finally appeared before us, resembling a depraved Ayasofia with electricity pylons standing in place of minarets. We reached the end of the road to find a guard sitting at a picnic table. I recalled bloggers’ accounts of arriving only to be informed by said guard that photographs were expressly prohibited. William told us to sit tight. He approached the guard and I could hear his colloquial Spanish faintly in the distance. His arms gestured back toward the car repeatedly. The guard sat hunched over the table, stone faced. A tense couple of minutes passed until William jogged back over, jumped into the driver seat, and said in a somewhat apologetic tone that we could not enter the reactor, but we could snap pictures from the outside.

For the remainder of the 1990s, Cuba and Russia made pleas to other nations for the $750 million necessary to complete construction. Their attempts were unsuccessful. The Clinton Administration and various U.S. environmental groups expressed concern over having a Soviet-built nuclear facility only 300 miles from Miami. Moreover, Cuban nuclear workers who defected to the U.S. expressed concern over the project’s safety in a report to Congress. These actions, as well as the U.S. embargo of Cuba are said to have discouraged other nations from getting involved. Tensions reportedly grew between Castro and Russian President Boris Yeltsin (and later, Vladimir Putin) over Cuba’s Soviet-era debt, which was estimated to be upwards of $20 billion. Public-private partnerships with companies such as Siemens were equally unsuccessful. The two nations formally abandoned the project in 2000.

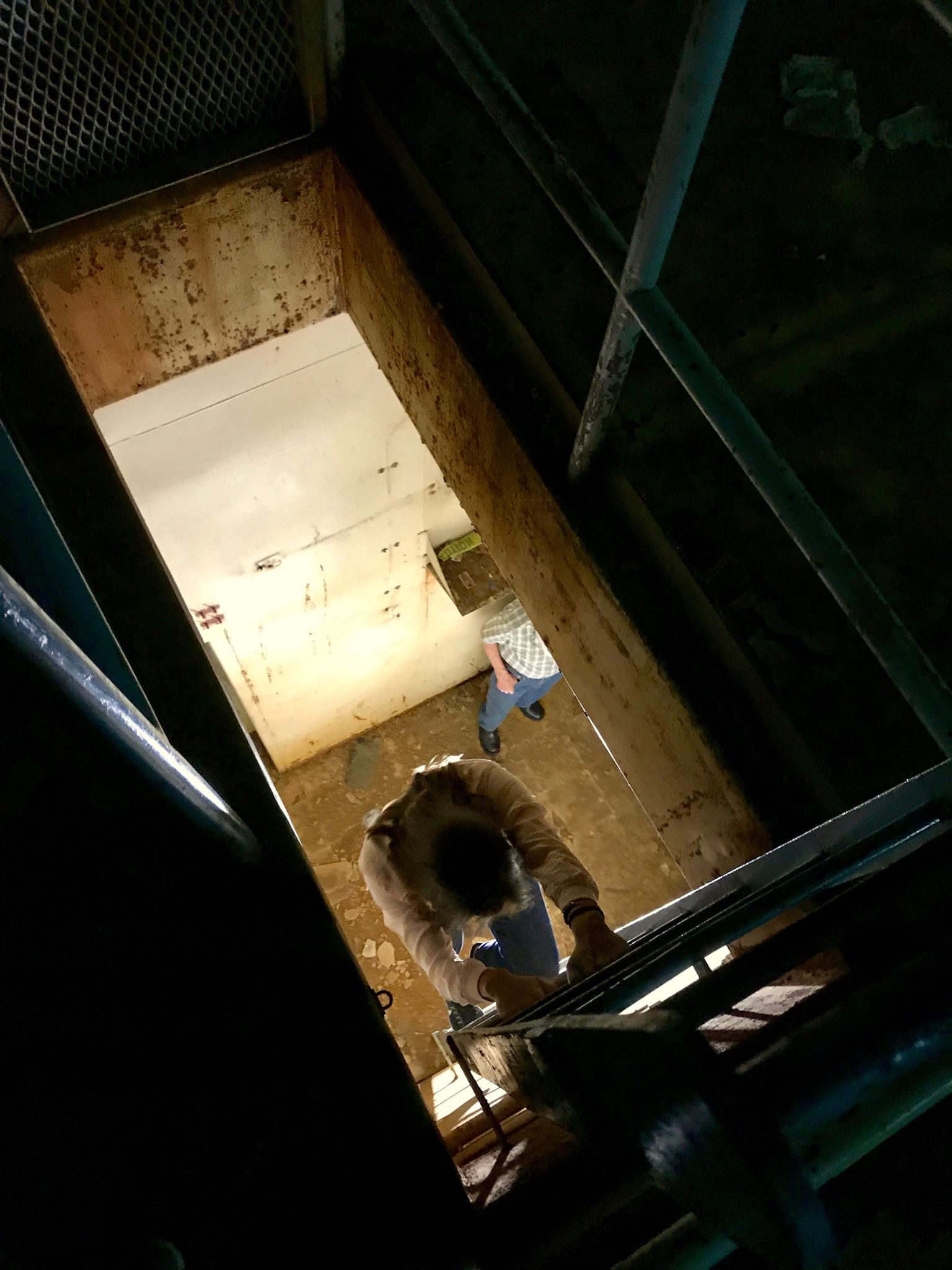

As we hopped out of the taxi I waved to the guard to express my thanks. William began conversing with him as we explored the perimeter. To the left was a mysterious staircase. I locked eyes with the guard and pointed up to it. He nodded back. I proceeded up the stairs and stumbled upon a dilapidated two-story concrete structure that contained half-completed shower stalls, blue tiles chipping at the edges. These perhaps would have been the decontamination facilities that the plant’s employees would have used to remove radioactive particles from the skin and hair in the event of exposure.

We then trudged through the overgrown vegetation toward the massive concrete shell of the reactor building, its surface stained with streaks of rust and mold, its perimeter wall flanked by barbed wire. Exposed rebar jutted up from its incomplete sections. After taking in the sight of the towering reactor, its rusted bones and unfinished edges stark against the clear blue sky and tropical greenery, we piled back into the Lada.

Down the road, another 5.5 km, we found our next destination: Ciudad Nuclear. As with cities like Pripyat and Visaginas, it was to provide the most modern amenities for its residents. Even in this derelict state, its past promise was evident. A grand boulevard lined with rusted-out streetlamps opened itself to the concrete shells of high-rise apartment buildings that sit idle amid the overgrown tropical flora. Inside, graffiti ranged from phalluses to inspirational José Martí quotes. In the distance sat apartment buildings that hundreds of resilient Cubans had reclaimed, as evidenced by the colorful linens strewn from the balconies. In the shadow of a blanched, crumbling five-story structure, a lone chestnut-coated horse grazed on what would have been the building’s front garden.

Curious to see more, we made our way through the deserted corridors of these modernist structures. Exposed beams stabbed through cracked tiles. One hulking twin-tower building stood unfinished. Its upper floors opened to the sky with no windows or balconies, an ambitious construction project halted midstream. At its base, political graffiti including “¡Resistir y vencer!” (“Resist and overcome!”), “Cuba libre” (“Free Cuba”), and “Se Lucha, Patria Libre” (“We fight for a free homeland”) clung to the walls. These promises of ideological endurance stood in the face of this unfulfilled material promise.

Back at the car, before the nearly three-hour drive back to Havana, Becca and William conversed in broken English and broken Spanish about the prospect of nuclear power in Cuba. “Muy peligroso” was William’s refrain. When we brought up comparisons to Ukraine’s Chernobyl (“es como Ucrania”), William balked, “No es como Ucrania.” He then punctuated the phrase “Nosotros no” with a sound effect and a sweeping gesture that symbolized a detonation. He seemed to imply that while Chernobyl was given the chance to explode catastrophically, Juraguá was not, his relief evident as he pressed a palm to his chest.

Juraguá remains a prospect on the horizon, symbolic of many possible futures that never came to be: a nation’s once-ambitious quest for energy independence, technological prowess following revolution, and, for some, narrowly averted nuclear disaster. In this way, it is suggestive of how some destinations may be tangible yet at the same time unreachable.